South Bend Watch Company

Location: 1720 E. Mishawaka Ave., South Bend

Written by Paul Berg

The story of the South Bend Watch Company unfolds in 1876 when Dietrich Gruen and some other enterprising artisans organized the Columbus (Ohio) Watch Manufacturing Company, later to be known as the Columbus Watch Company. This firm was successful for 17 years, but in 1902, for reasons unknown, it was sold. The purchase was promoted by three Studebaker brothers: George, Clement, Jr., and J.M., who were sons of Clement, Sr., one of the five famous Studebakers who founded the wagon and car business. The business was moved to South Bend, and the name American National Watch Company was first proposed, but logically the name South Bend Watch Company was finally chosen. Personal financial notes were given by the Studebaker brothers for the acquisition.

George Studebaker

Clement Studebaker, Jr. and his children

J.M. Studebaker, Jr.

The new firm was organized in June 1902, and a site chosen on the 24th of that month. Incorporation under the laws of New Jersey is dated July 24, 1902, with a capital stock of $132,000. Management comprised Clement, Jr., President; M.V. Beiger, Vice President; Irving A. Sibley, Treasurer; and E.A. Bazzett, General Manager and Secretary. Besides these men, the following were on the board of directors: H.H. Gross, F.S. Fish, William Reel, Frederick Lazarus, Charles W. Haldy, Albert O. Glock and Charles Clie.

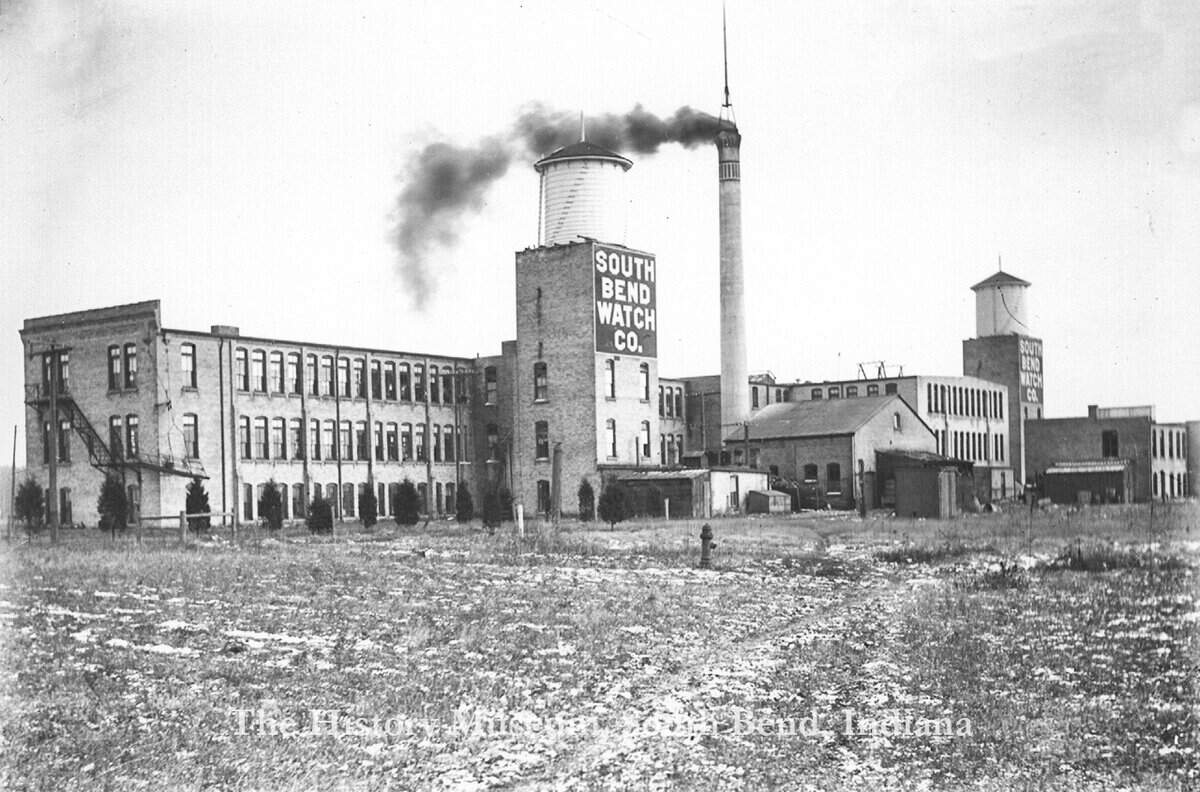

A beautiful factory was built on a ten-acre tract of land in the River Park suburb of South Bend, at 1706-1720 Mishawaka Avenue, about half-way between South Bend and Mishawaka. The building to house the new firm was three stories, of fireproof construction and measured 60 feet wide by 450 feet long. Construction started in August 1902 and was under the supervision of H.D. Johnson. Large fireproof vaults were installed in each department, and the factory was equipped with automatic sprinklers. Separate buildings were constructed for the dial and gilding and the boiler room. The building site was purchased from J.M. Studebaker, Sr.

According to The South Bend Tribune issue of March 29, 1903, President Clement Studebaker, Jr. pushed an ivory-tipped button at 10:00 a.m. the previous day, sending an electric impulse through the new million-dollar plant. A group of 145 workers, mostly German watchmakers, had moved from Columbus, Ohio, to help produce the new watch that later was to reach a production of 60,000 watches per year.

Clement Studebaker, Sr. died in 1901, and his wife shortly after. Their heirs were George and Clement Jr., who later became important members in the firm, and a sister, Mrs. Anne Carlisle. By 1910, J.M. Studebaker had gained over 50% of the stock, and with the death of Clement Jr., total management responsibilities passed to him. J.M. died about 1918, and Mr. Witwer, a nephew, was appointed executor of the estate. At this time, the interests of Witwer and J.M. Studebaker were sold to George and Clement, Jr.

During World War I, the company took an active part in the war effort, supplying gun parts to Canada.

In 1920, the Studebaker Mail Order Company, Chicago, was formed to become a holding company for the South Bend Watch Company, the Studebaker Watch Company (incorporated in 1923), and the Studebaker Watch Company of Canada, Ltd. (incorporated in 1924). The Studebaker Mail Order Company also held a controlling interest in the Studebaker Stores, Inc., established in 1923 and in 1929, a firm known as Colin B. Kennedy, Inc., Highland, Ill., manufactured radios. The holding company was reported to have operated 25 retail stores. Officers in the firm in 1920 were G.M. Studebaker, President; F.M. Wellington, Vice President and Treasurer; and J.J. Seerley, Secretary. Clement Studebaker, Jr., Clement Studebaker, III, and Scott Brown were listed with the officers as being on the board of directors. Clement Studebaker III was the president of the Studebaker Watch Company.

In 1909, when the Studebaker Brothers Manufacturing Company, car and wagon manufacturers, was incorporated, Clement and J.M. Studebaker and their immediate families acquired large blocks of stock, but far from a controlling interest. They did not take part in the company’s management, nor did the car firm have any interest in the watch firm.

The South Bend Watch Company was to establish a fine reputation in watchmaking, directing its production to fulfilling the railroad-grade requirements that were in demand. Their literature stated they sold only to accredited dealers, and before filling an order the buyer was scrutinized. The watch became well known as the purple-ribbon watch. The box that contained the watch was supplied with a purple ribbon placed across the watch. Earlier their advertisements had shown a watch in a cake of ice with a statement, “every South Bend Watch must stand the ice test” and a story circulated through the plant that a dealer had written, complaining that the watches may run in a cake of ice but they would not run in his customer’s pants.

An important person in the early design of the South Bend watches was Charles T. Higginbotham, who had to his credit the prize-winning “Maiden Lane” by Seth Thomas. The well-known watch designer had been employed by the Columbus Watch Company and came to South Bend as Consulting Superintendent. He authored ten articles for his new employers, such as “Short Talks to Watchmakers” and “The Making of a Marvelous Mechanism,” the last a description of a trip through the factory.

The first models were full-plate, and the similarity to the Columbus watch is striking. It is of interest that the South Bend watch started serial numbering at around 370,000 where the Columbus numbers left off; however, it should be noted that a few Columbus watches have appeared in the 500,000’s, so they must have had an erratic numbering system.

One of the early high-grade watches designed for railroad service was the Studebaker model. The first models were full-plate, 17 and 21 jewels, in 16 and 18 sizes and were accompanied by a certificate insuring against the cost of any changes to meet railroad requirements for five years. A watch named Studebaker is immediately associated with the car, but since the company was owned by people named Studebaker, it is more logical the name came from the owners. Also, the Studebaker model watch had been named before the car had reached any significance.

The high-grade watch made by South Bend Watch Company was the ¾-plate 16 size Polaris, a 21-jewel movement which was in open face type only. This movement was guaranteed against factory defects forever, and a coupon accompanied the watch allowing any recognized agent to repair without charge to the owner. This watch was listed at $100.00 (almost $2,400.00 in 2015 money!) in the 1913 catalog but does not appear in later catalogs.

The 227 grade, 16 size, 21 jewel Special Railroad watch was another high-grade movement being made in the bridge model and was first listed in the 1916 catalog.

Another important model was the 12 size Chesterfield, which came with 15, 17 and 21 jewels. This model, which can be identified by the case marking, was early and continued to be featured up through the 1920s. Late models that deserve mention were: the Adams, Waldorf, Virginian, Georgian, Wellington, Madison and General. These were complete watches, and the name described the type of case and the movement. The company called their movements models 1, 2 and 3 and grades from 100 up to 655. The odd numbers were for open-face cases and the even for hunting cases. In the early catalogs, the movements were listed separately from the cases. The lowest-priced watch was a size 16, 7-jewel watch priced at $6.75 and was called the 203 grade.

The company listed their watch cases by such names as: Pyramid, Pilgrim, Panama and Silvaloy. Cases with French Pendants were equipped with their featured Kant-Kum-Off bows. The company also offered a handsome Handibox to convert their watch into a desk clock as a sales promotion feature. The extent of the company’s sales efforts may be appreciated from the fact that they frequently carried a full-page advertisement in the Saturday Evening Post.

As previously mentioned, in 1923 the Studebaker Watch Company was incorporated and now the company was to wear two hats, one the South Bend Watch Company which continued to make a fine line of watches sold through dealers and the other the Studebaker Watch Company, a mail order enterprise offering a wide variety of merchandise such as rings, charms, bracelets, necklaces of pearls, fancy pocket knives and jewels. In their catalog were offered imported wristwatches and a Studebaker pocket watch. The new Studebaker was a 17 or 21 jewel watch and had the features of its predecessor, but shortcuts were taken in production to lower costs, and the watch was not the same grade nor did it bear a grade stamping. How were the watches offered? Direct to the customer with $5 down and $3.50 per month until paid for. A booklet for keeping records of the payments was given to the customer. The buyer only had to get the signatures of three business people or banks to establish credit. This was found to be an insecure method of selling, and too many accounts went unpaid.

The letterhead for the Studebaker Watch Company shows an artist’s rendering of the plant with the firm name. The same rendering had been used, showing the name South Bend Watch Company.

An item in The South Bend News-Times of April 22, 1928, announced the formal opening of a new retail jewelry store that had been attended by 7,000, and 5,000 souvenirs were given away, such as watch fobs. On October 18, 1928, the same newspaper carried a story of an autumn exposition held at the store. This was probably the Studebaker Stores, Inc., which had been mentioned before.

On the evening before Thanksgiving Day 1929, the company posted a bulletin stating they would shut down on the last day of the year. Liquidation began on January 31, 1932, and by 1933 all assets had been sold and the creditors were paid off at 50 cents to the dollar. The factory building was to serve several patrons until July 8, 1957, when a fire did so much damage that the only result was to raze the structure.

Thus ended Indiana’s only watch-making company, which in 26 years had produced over one million watches and had paid over $20,000,000 in wages. It, like many other famous American watch firms, learned that the end of the 1920s was the end of the pocket watch era and that they could not compete with the European market in the new fad of wristwatches.

The lapse of 40 years since this company went out of business has erased many interesting facets about the company, but perhaps this story will bring to light some missing information that should be added to the South Bend Watch Company story.