Singer Sewing Machine Company

Isaac M. Singer established his Singer Company in 1851 in Boston. His operations were moved to New York City in 1853. In 1858, the plants in New York were established in an area surrounded by Mott, Spring, Delancy, and Broome Streets. In 1872, the main plants were moved to Elizabeth, New Jersey.

Around 1864, the western agents of the Singer company were having trouble getting machines from the Chicago distributor. Fred Grettner, the South Bend agent, and the Chicago agent thought they could get local furniture factories to bid on cabinet construction (because the sewing machines were installed in a wooden case with a foot pedal for operation). Apparently at this time Singer sewing machine cabinets were not built by Singer, but on contract with other manufacturers. Grettner approached several South Bend furniture makers, such as B.F. Price, Smith & Rilling, and Montgomery, for bids on 5,000 to 10,000 cabinets per month. This would include tables, box covers, and drawers. All those approached refused to bid; Grettner implied that they did not want such small work.

Because South Bend was the center of black walnut production, it was an excellent location for furniture making. In 1868, Leighton Pine came from the New York Singer office to establish a Singer cabinet factory in the South Bend area. He selected a site on the East Race, owned by a Mrs. Sherland, which was purchased for $2,500. The town of Mishawaka, wishing to get the factory for their city, offered Pine and the other Singer officials who inspected the South Bend site better water power, factory site, and 20 additional acres, all free. The officials accepted the offer and even directed Grettner to move his distribution center to Mishawaka. Grettner decided to raise the money to pay Mrs. Sherland for the South Bend site by subscription from South Bend citizens, and persuaded Miller & Greene, proprietors of the East Race water power, to offer free power to Singer. This offer was sent to the officials who had returned to New York, and it was accepted. Grettner had not even raised all the funds for his subscription yet, some of which was coming in $.25 pledges. Eventually, all funds were raised, and Singer came to South Bend.

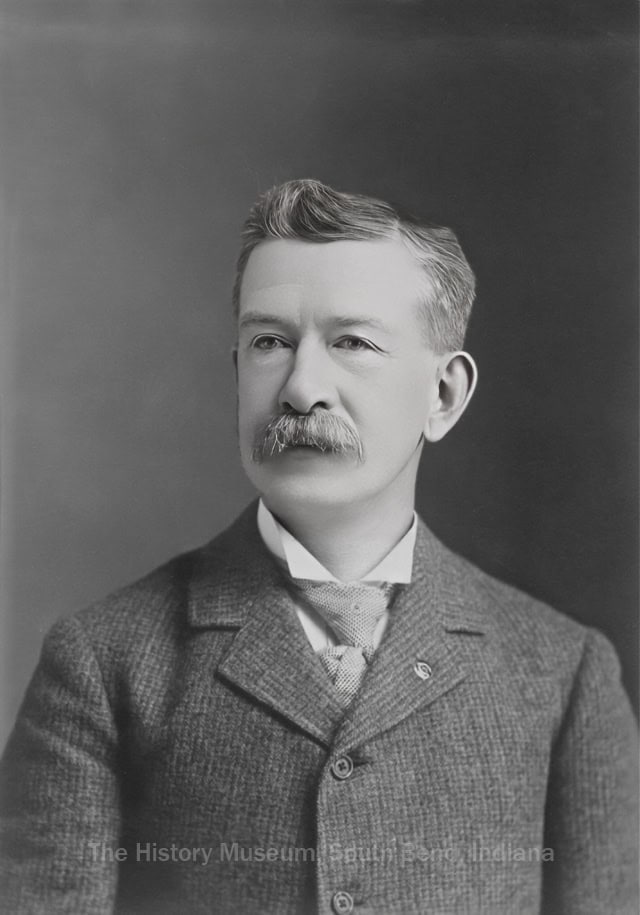

In 1875, Pine left Singer and became a general manager at the South Bend Ironworks. In November 1879, he returned to Singer and stayed with the firm until his death in 1905. While working for the Singer Sewing Machine Company, Pine became involved with at least two other South Bend business ventures, the Economist Plow Company and the Spring Curry Comb Company. Eventually, Pine became general manager of all Singer cabinet factories in Cairo, IL; Kilbourne, Scotland; Wittenberg, Germany; Floridsdorf, Austria; and Podolsk and Moscow, Russia. He continued to live in South Bend, but died in 1905 while on a business trip to Scotland.

Leighton Pine took an active role in community affairs. One unsuccessful venture was to establish the Cushman Telephone Company to compete against the Bell Telephone Company.

Pine was successful in his campaign to establish a standpipe water storage system, over the Holly system favored by John M. Studebaker. This issue was one of the hottest contested issues of the 1872 mayoral race. The standpipe advocates won the election, and the standpipe was constructed. On Christmas Day 1873, a wager was established between Pine and Studebaker. Pine bet Studebaker he could drive Studebaker from the belfry on the Studebaker factory office (approximately 6 stories off the ground) with water from a hydrant near the factory (water pressure being supplied by the newly installed standpipe), while several other hydrants in the area were opened. This would finally prove that the standpipe system produced enough pressure to pump water effectively, which the Holly system advocates did not believe. Pine turned on the water and immediately drove J.M. Studebaker and his friends from the belfry. The prize brought forth in the bet was a cow, which was turned over to the Ladies Benevolent Aid Society for the benefit of the poor.

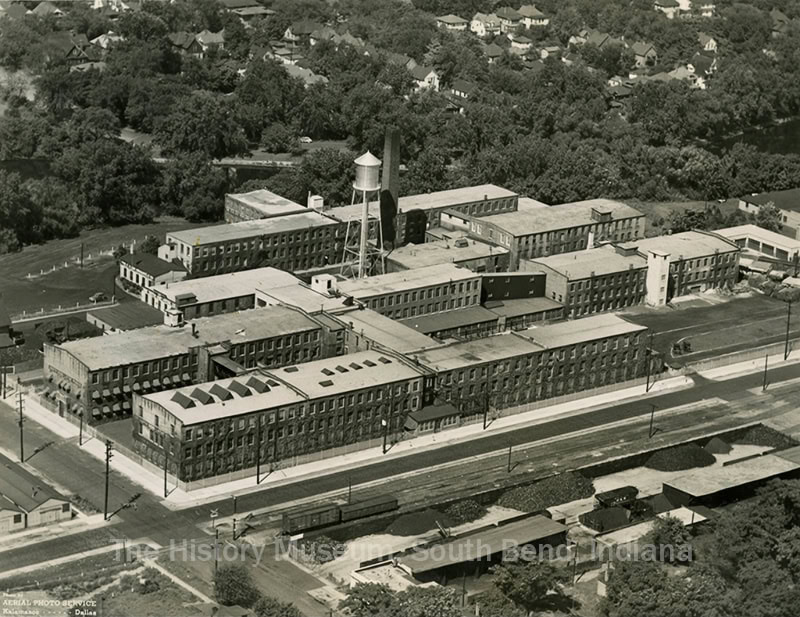

By 1891, the Singer Sewing Machine Company in South Bend had 898 employees, and by 1900 the facilities along the

The new plant allowed Singer to expand operations greatly in South Bend. The South Bend plant was already a distribution center and this function grew. By 1907, 10,000 sewing machine cabinet sets were manufactured per day. Only part of these were completely finished; numerous sets were shipped to Scotland “in part white,” that is, unfinished and unassembled. Of the finished sets, half were sent to Elizabeth, New Jersey, to have the machines installed and to be shipped to the U.S. seaboard, South America, and Asia. Machines were sent from Elizabeth to be installed at South Bend, and the completed sewing machines distributed from here. The cabinet work was done to very close tolerances so that parts would be interchangeable, no matter where they were shipped.

The year 1914 was the peak year for production in South Bend. There were about 3,000 employees working at the Division Street plant. In the early years of the 20th century, about 50 million feet of hardwood lumber for cabinets, 20 million feet of softwood lumber for packing boxes, and 10 million feet of walnut, oak, gum for veneer were used in the South Bend plant per year. This was all stockpiled at the huge 20-acre lumberyards adjoining the factory. David Pollack, a Singer researcher, estimated that three-quarters of all sewing machine cases and cabinets in the world were made in South Bend, with a yearly output of 2,000,000 cabinets.

After 1914, changes occurred which affected the operation in South Bend. The plants in Germany became self-sustaining, and Scotland was getting close to self-sustaining. They could buy European lumber at a better price than the cost of shipping it from the United States. Of course, the plants in Russia were lost because of the Russian Revolution. These plants had received numerous cabinets from the U.S. Within the U.S., it became more economical to dry and rough cut lumber at the Singer plant near Trumann, Arkansas, which was closer to a lumber supply and to apply veneer at the plant in Cairo, IL. These developments cut into the work done at South Bend. Stockpiling of lumber ceased in 1933, and the lumberyard employment reduced to zero from a 1913 high of 224 workers. The foundry operation could be more effectively handled in Elizabeth, NJ, since the electric machine did not need cast treadles and stands any longer. The foundry buildings (which used to belong to the Economist Plow Company) were sold in 1937.

The Depression years were not good for Singer in South Bend (nor anywhere). In 1932 there were 650 employees, and most of these employees worked a 16-hour-a-week schedule. There was some growth after this, but throughout the 1930s there were only around 800 or 900 employees. They were mostly on a 40-hour work week in the later years. In 1938, the factory was unionized, and Local 917 of the United Electrical, Radio & Machine Workers was established. By the beginning of World War II, there were 1,200 employees.

There seem to have been only two strikes at the Singer factory. The first one was in 1902, where there was a controversy over who should name the assistant plant manager. In 1939, the newly unionized employees started a strike at the plant over the hiring practices of the company. The employees wanted laid-off workers hired back into new positions rather than new people. This strike started on April 11, 1939, because a 19-year-old girl with no previous experience had been hired. The strike continued until May, when the workers returned to work, the girl was re-hired and the strike was resumed after one day of working. The strike was finally called off on July 23, 1939. This time the controversial girl was not re-hired, but apparently none of the other issues were resolved. At this time, the 800 production workers were working a 3-day workweek.

The Singer company in South Bend had problems with conversion to wartime production during World War II since there was not a great demand for wood products for defense. The main products from the plant were wooden packing crates for guns and other material and plywood sub-assemblies for planes and gliders. Such products as gunstocks and wooden propellers were rejected as inappropriate. There were fewer workers at the South Bend plant than before the war, and those that were employed were not using the peak of their skills.

In July 1945, Singer was given permission to return to domestic production limitedly. There were 500 employees left at the plant because of the lack of war work available and suitable for the cabinet works. Management expected this number to rise to about 1,300 with the resumption of civilian work. The main problem in converting back to civilian production was the lack of raw material available to the South Bend plant.

After World War II, things never got back to normal at the South Bend plant. A strike at the New Jersey plant in 1949 cut off the supply of sewing machine heads and so reduced the need for cabinets made in South Bend. Numerous workers were laid off. In April 1954, they announced the closing of the South Bend plant. The reason given was to merge the cabinet work at plants nearer to the lumber supply. This had of course, been under way since 1914. The 90-day shutdown process began in January 1955.

Today, there is only one building remaining at the Western Avenue Singer plant. It is currently known as the Mary Crest Building.

Users may download material displayed on this site for noncommercial, educational purposes only, provided all copyright and other proprietary notices contained on the materials are retained. Unauthorized use of the Northern Indiana Historical Society d/b/a The History Museum’s logo and Web site logo is not permitted. The contents of this site may not be used for commercial purposes, without written permission of the Northern Indiana Historical Society d/b/a The History Museum. To obtain permission to reproduce information on this site, submit the specifics of your request in writing to Director of Marketing & Community Relations, The History Museum, 808 West Washington Street, South Bend, Indiana 46601 or If permission is granted, the wording “provided with permission from the The History Museum” and the date must be noted. However, permission is not required to create a link to the The History Museum’s Web site or any pages contained therein.