Indiana, a State of Change

Since 1860 there was a large growth of industries in Indiana. As a result, people came from the U.S. and abroad to work in these new factories. By 1920, the growth of Indiana’s cities had begun.

In South Bend, James Oliver, the inventor of the Oliver Chilled Plow, started a factory to manufacture farm implements. People, many from other countries, migrated to northern Indiana to work in his factory. The Studebaker brothers had started, first, a blacksmith shop that eventually grew into the largest wagon manufacturer in the world (and then on to automobile manufacturing). These new factories needed huge amounts of laborers to keep the manufacturing process running.

To learn more about James Oliver click here

To learn more about the Studebaker Company, visit: http://www.studebakermuseum.org

Specialized factories helped make other cities grow. Steamboats were made in Jeffersonville alongside the Ohio River. Many Elkhart factories centered around making band instruments. In 1891 the Wayne Knitting Mills in Fort Wayne began making socks and clothing.

Around 1900 natural gas was discovered near Portland, Indiana. The northeast side of the state saw growth centered around this new energy resource. The Indiana state government offered free gas (to run machinery and other things) to factories that would build in these areas. Natural gas allowed for the production of glass products.

Unfortunately, the natural gas discovered in northeast Indiana only lasted about 15 years. Factories then switched to using coal for their energy needs. They continued to use sand and clay to make everything from glass to pottery.

Steel is King

With the technological advances in industrial production, steel making had become an important occupation in Indiana. Steel was now being used in buildings, homes and the flourishing railroads. There are three basic elements needed to make coal: iron ore, coal and limestone. A certain type of coal is burned and turned into a fuel called coke. Coke burns at very high temperatures that is needed to melt large quantities of iron ore and limestone. When iron ore and limestone are combined and heated together at high temperature, the useable steel settles towards the bottom of the kettle and limestone forms with the impurities and floats at the top of the heated mixture (this is then skimmed off the top of the molten steel and discarded).

Around 1900 the United States Steel Company began looking for a location to build a new steel mill. The plant had to be located in an area close to large supplies of iron ore, limestone and coke (coal) and had to have a way of getting the finished steel to places where it could be used. United States Steel decided to build their new factory on the sand dunes beside Lake Michigan. By placing the factory here ships could travel to the new factory by way of Lake Michigan to deliver the iron ore. Railroads already existed that could bring the limestone from southern Indiana to the shore of Lake Michigan. Coal and its by-product coke could be delivered by train from Pennsylvania (Indiana’s coal supply could not be used to make coke).

This new city was named Gary after Elbert H. Gary, the president of the United States Steel Company. After U.S. Steel built the factory at Gary several other factories and companies came to Gary (often called the Calumet Region of Indiana). Gary became a major industrial center that lasted for decades.

You can view an excellent photo collection of U.S. Steel’s Gary plant by visiting: http://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/ussteel/

The Automobile and Indiana

Now that steel production was cheap and easy to produce, Henry Ford’s invention of the modern factory production line and interchangeable parts would take full advantage of the steel industry. Nothing in our century has changed life so dramatically as the invention of the automobile. For many years Indiana was the center of the automobile industry.

Automobiles were produced in more than 40 cities within Indiana. The largest of the Indiana automobile manufacturers was the Studebaker Company. It produced its first car in 1901. The company continued making automobiles until they closed in 1963, after more than 60 years in the automobile business.

Other famous automobile companies in Indiana included:

Elwood Haynes partners, the Apperson brothers, produced cars of their own called the Apperson Jack Rabbit. The company went out of business in 1925.

Indianapolis was also the center for what became the most famous auto race in the world. The Indianapolis 500 was first held on Memorial Day of

The track has four turns that bank at 9 degrees each and measure 440 yards from entrance and exit of each turn. These four turns were then connected with long straights that make the track exactly 2.5 miles in length. The original surface of the track was crushed stone and tar that proved to be very dangerous on the first opening race. In August of 1909, 3,200,000 paving bricks were installed, laid on their sides in a bed of sand and fixed with mortar. This gave the speedway the immortal nickname, “The Brickyard.”

Poor attendance at several races throughout the year in 1910 caused the owners to redesign their racing plans. They decided on one, single race in 1911. They envisioned this race with a huge audience and offering the winner of the race a huge monetary prize. On May 30, 1911 the first Indianapolis 500 mile race occurred, offering the winner a purse of $14,250. With the exception of an additional race in September of 1916, no race other than the Indianapolis 500 was to be held until the addition of the popular NASCAR stock car event, the Brickyard 400 that debuted in 1994. The 500 was suspended during America’s involvement in two world wars, 1917-1918 and 1942-1945, but held in all other years.

To learn more about the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and all the events held there visit http://www.indy500.com

You can also visit the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum by visiting http://www.indianapolismotorspeedway.com/facility/35204-Museum/

Changes After World War One

By 1920 the three leading industries in Indiana were iron and steel, automobiles and railroad cars. More Hoosiers worked in factories than worked on farms. A new industry was soon created in Indiana-the manufacturing of electrical products. During the 1920s the first electric stoves, refrigerators and radios were sold for the first time. Homes and businesses across Indiana were soon lighted by electricity that replaced gas and kerosene lanterns as lighting.

The Great Depression

Many farmers could no longer afford to pay their mortgages and lost their land. In 1933, 5% of the nation’s farms underwent mortgage foreclosures. The stifled economy also drastically reduced the quantity of goods and services bought and sold. The industrial and financial urban centers suffered from vast numbers of business failures that led to the closure of 30,000 businesses nationwide. Banks closed their doors because of the lack of cash. Production stopped in the industrial sector as a result of falling investments and an inability to pay workers.

These closings and shutdowns led to a huge unemployment crisis. Unemployment reached a high of 25% in 1933, and hovered between 15% and 20% for the remainder of the 1930s. Small, rural towns were hardest hit, as were unskilled workers and minorities. Abject poverty quickly appeared. Children started receiving inadequate nutrition and healthcare, and starvation became an everyday occurrence. The unemployed were usually evicted from their homes and left to wander around homeless or to live in poorly constructed shelters made of any trash material that could be found. Many were so ashamed of their new lowered status that they committed suicide. The suicide rate in the U.S. rose 30% between 1928 and 1932.

Of all the problems Indiana’s Governor Paul McNutt and most public officials faced in the 1930s, public relief was the most important. With tens of thousands of Hoosiers unemployed, relief agencies and public officials were flooded with unprecedented demands for food, clothing, medical care and jobs. Bread lines and soup kitchens were created and constantly used.

Prior to the Depression, local communities, private and religious organizations typically controlled relief and charity. There was no real state, or federal level of financial help or aid. By 1930 local charity organizations began to focus upon Depression relief. However, because of the large amount of relief needed, these local charities soon became overwhelmed and many had to stop their operation.

By 1933 the federal government had started the Public Works Administration (PWA) that was designed to get people back to work building large-scale projects such as water and sewage treatment facilities, highways and public housing. In 1935 the major federal welfare program Works Progress Administration (WPA) was created. The main goal of the WPA was to provide a job for all able-body workers. The WPA began in Indiana by July of 1935. By October 74,708 Hoosiers were on the work rolls. Census figures indicated that by March of 1940, 64,700 of Indiana’s 172,000 unemployed workers were working on WPA projects.

The WPA-Works Progress Administration

Hoosier men and women worked on a wide variety of WPA projects within Indiana. A majority of workers were employed in the building and improvement of the state’s highways, roads and streets. These street projects involved new shoulders, ditches, culverts, bridges and curbs. The WPA workers also built water treatment plants, flood control projects (i.e. Monroe Reservoir) and public swimming pools. Nearly every Indiana city and community had something that was constructed by the WPA.

A little-known area of the WPA is that some projects did not require physical labor. Several WPA workers indexed public library collections, newspapers and county histories. “Indiana artists found employment in producing public art, the most notable examples of which were the murals done in many post offices across the state.”

Every Hoosier was affected by the Depression. A whole generation of Hoosiers spent the remainder of their lives storing food, money and clothing with the fear that the Depression may happen again. Hoosiers also became strongly reliant on the state’s help for finding employment to obtaining basic needs in a personal crisis. The generation that lived during the Depression has been termed the ‘tough generation’ which is more than appropriate.

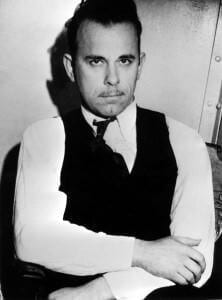

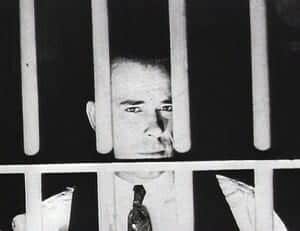

The Depression Era Robin Hood

While a teenager, John exhibited traits that troubled many of those he came in contact. Eventually quitting school to work in an Indianapolis machine shop. Surprisingly, John worked very hard at his job, but would stay out all night partying. This alarmed his father who felt the big city was corrupting his son and the Dillinger family soon moved to Mooresville, Indiana.

After getting married quickly John had a hard time adjusting to family life and the marriage ended in 1929. After the market crashed in 1929, John found it almost impossible to find a steady job as like thousands of other Hoosiers. He soon began planning to rob a bank with his friend Ed Singleton. The two never made it to the bank, but did rob a local Mooresville grocery store making away with $50. They were both spotted leaving the scene by a minister who recognized them both and reported what he saw to the police. John and Ed were arrested the next day. Singleton pleaded not guilty, but John’s father convinced him to be honest and plead guilty. Dillinger was convicted of assault and battery and conspiracy to commit a felony. He was sentenced to 10 to 20 years in prison.

While incarcerated at the Indiana State Prison in Michigan City, Indiana, John Dillinger embraced the criminal lifestyle. He made several criminal ‘contacts’ while at the the state prison and they would come in handy several times throughout his life of crime.

After being paroled, he returned to his ‘training’ as a career criminal.

During John Dillinger’s reign of terror, he robbed at least two dozen banks,

After spending nearly a year running from the police and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Dillinger was wounded in a gun battle and returned to Mooresville and hid out in his father’s house. He soon returned to Chicago in July of 1934.

John Dillinger’s body was sent back to Mooresville where he was eventually buried at Crown Hill Cemetery, Indianapolis.

References Used

“Onset of the Great Depression.” SparkNotes. Accessed June 29, 2015. http://www.sparknotes.com/.

Carmony, Donald F. A Brief History of Indiana. Indiana Historical Bureau. Indianapolis, 1961.

Furlong, Patrick Joseph, and Mary Ellen Gadski. Indiana: An Illustrated History. Sun Valley, CA: American Historical Press, 2001.

Howard, T. E. (1907). A History of St. Joseph County, Indiana, Both Volumes. Chicago, IL: Lewis Publishing Company.

Madison, James H. Indiana through Tradition and Change. Indianapolis, Indiana: Indiana Historical Soc., 1982.

Scoville, Warren Candler. Revolution in Glassmaking. Entrepreneurship and Technological Change in the American Industry, 1880-1920.Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1948.