Early South Bend

St. Joseph County was formally created in 1830, with four original townships. Lathrop Taylor and Alexis Coquillard plotted the town of South Bend in 1831. Most of the inhabitants of the town were tavern owners, merchants, or fur traders. The population of South Bend in 1831 was around 128 men, women, and children. This is the original wording of the court record:

State of Indiana, St. Joseph County, ss.:

On this 28th day of March, A.D. 1831, Alexis Coquillard and Lathrop M. Taylor, the proprietors named in the foregoing instrument and town plat of the town of South Bend, personally appeared before me, one of the associate judges of the St. Joseph circuit court in and for said county, and severally acknowledged the signing and sealing of the aforesaid plat, to be their own free act and deed for the purposes therein expressed.

Given under my hand and seal the day and year first above written.

William Brookfield,

Ass’t J.C.C.

The first industry in South Bend was developed in the in the late 1830’s. Some of the first factories were glass factories, but their product was so poor in quality, the companies did not last. However, in the middle of the 1840’s, industry began to grow around the South Bend area, especially along the St. Joseph River. The early industries were located on two races (or man-made canals), one on each side of the St. Joseph River in downtown South Bend. The race on the east side was known as the East Race and it covered an area bounded by the St. Joseph River, Niles Avenue, Madison Street, and Corby Street. The race on the west side of the river was known as the West Race and runs next to the South Bend Century Center. The industries harnessed waterpower for their production needs. Many of the major industries started on one of the two races before relocated to other locations after the development of electric power.

In 1846 another village was platted and added to St. Joseph County. The town of Lowell, Indiana was formed and covered the area between Washington Street to just north of Cedar Street; the river to just east of Hill Street. The founders of Lowell hoped to capture the success of industry of its namesake, Lowell, Massachusetts. However, in 1867 South Bend annexed the town of Lowell and it ceased to exist.

Electricity

The first electric producing plant in South Bend had to be tied to the East and West Race along the St. Joseph River. The partnership of Abraham Harper, William Patterson, and Lathrop Taylor into the South Bend Manufacturing Company brought the first usable dam to the St. Joseph River in 1842. The South Bend Hydraulic Company had ownership of the water proceeding down the East Race. A steam-powered generator was used on the East Race to produce vast quantities of power that lighted and heated most of the city of Mishawaka and South Bend. In 1903 the ownership of the West Race was purchased by James Oliver, founder of the Oliver Chilled Plow Company. The Oliver Chilled Plow Company constructed a power plant on the West Race (which the foundation of the old power plant can still be seen). The power plant was so efficient and powerful that it supplied electricity for light, heat, and power to the Oliver Opera House, Oliver Hotel, factories, and other Oliver properties. These power plants remained on the races of the St. Joseph River until the invention of self-contained coal/steam driven generators that allowed companies to move away from the East and West Race.

Transportation

The first locomotive to reach Mishawaka and South Bend roared into town the evening of October 4, 1851, when the locomotive, John Stryker, came puffing into the stations to a grand collection of local citizens clapping and cheering. The South Bend Street Railway Company was formed in 1873 to investigate the feasibility of electric streetcars being constructed in South Bend. In 1882 the first overhead or trolley system was attempted-the first-time electrified streetcars were put into service anywhere in the world. However, the cars could only travel part of a city block because of the deterioration of electric current over a long expanse of wire (before electric transformers were used). In the latter part of 1882, after the electricity problem was solved, another streetcar company constructed an electric streetcar line from South Bend to Mishawaka (four miles) that was a successful enterprise.

Communication

The first telegraph line strung through northern Indiana was completed in 1847. However, because investors were slow to devote money to this endeavor, it was 1848 before South Bend was in communication with the whole country. The telegraph line was constructed between Buffalo, New York and Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

The telegraph soon gave way to the telephone. The South Bend Telephone exchange was authorized to erect poles and wires in March of 1880. The lines extended to include Mishawaka and other places outside of St. Joseph County. The first phones created were hooked into “party lines.” Party lines are where everyone’s phone on a city block is connected into the same line. Each household had its own ring pattern or sets of rings to alert the members of the home that they had a call. In 1899 the first direct dial (private line) phone was installed to the Oliver Chilled Plow Works factory office.

City Water

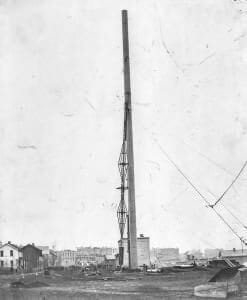

Most early residents of South Bend received drinking water from wells or the St. Joseph River itself. However, in 1871 there was a plan by the Holly Water Works Company to provide the city of South Bend with water that could be piped directly into homes (and provide water for fighting fires). The city turned down Holly Water Works Company in favor of the construction of a standpipe (or water tower). When the standpipe was pumped full of water the pressure (or weight) on the water mains throughout the city would be equal (there would be equal water pressure). The leader in support of the standpipe was Leighton Pine the superintendent of Singer Sewing Machine company (which had just recently moved to the East Race on Mr. Pine’s invitation). A huge debate between Mr. Pine and supporters of a reservoir-type water system raged for months. The standpipe finally won majority support in 1872 and Mr. Pine’s plan would be put into action.

The standpipe was constructed with the following dimensions and materials:

The standpipe was raised at the crossing of Pearl, Jefferson, and Carroll Streets in South Bend (which is now the parking lot of the Century Center). After the construction of the standpipe it had to be lifted into place. “The undertaking of lifting this mass of iron from the ground to perpendicular was the greatest engineering feat ever attempted in this part of the country. A like attempt at Toledo [Ohio] resulted in the falling and breaking of the stand pipe when it had been lifted half way up.” The raising of the standpipe began on Friday, November 14, 1873, which raised the pipe 22 feet off the ground. On Saturday, November 15 the raising continued until 4 p.m. when the standpipe reached an elevation of 70 degrees and

References Used

Pictorial and biographical memoirs of Elkhart and St. Joseph counties, Indiana, together with biographies of many prominent men of northern Indiana and of the whole state, both living and dead. (1893). Chicago, IL: Goodspeed.

Chapman & Company, C. C. (1880). History of St. Joseph County, Indiana: Together With Sketches of Its Cities, Villages and Townships, Educational, Religious, Civil, Military, and Political History; Portraits of Prominent Persons, and Biographies of Representative Citizens; History of Ind. Woburn, MA: UNIGRAPHIC.

Coquillard, M. (1920). Alexis Coquillard, His Time: A Story of the Founding of South Bend, Indiana. South Bend, IN: Northern Indiana Historical Society.

Howard, T. E. (1907). A History of St. Joseph County, Indiana, Both Volumes. Chicago, IL: Lewis Publishing Company.